Warsangali Sultanate

Warsangali Sultanate | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Possibly late 13th century–1887 | |||||||||

Map of the historic Warsangali Sultanate | |||||||||

| Capital | Las Khorey | ||||||||

| Common languages | Somali | ||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | Possibly late 13th century | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1887 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

• Total | 54,231 km2 (20,939 sq mi) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Somalia | ||||||||

The Warsangali Sultanate (Somali: Saldanadda Warsangeli, lit. 'Boqortooyada Warsangali', Arabic: سلطنة الورسنجلي), was a Somali imperial ruling house centered in northeastern and in some parts of southeastern Somalia. It governed an area historically known as Maakhir. [1]. The sultanate was ruled in the 19th century by the influential Sultan Mohamoud Ali Shire who assumed control during its most turbulent years. In 1884, the United Kingdom established the protectorate of British Somaliland through various treaties with the northern Somali sultanates (Dir, Isaaq and Harti including the Warsangali). The Warsangali clan constituted 120,000 of British Somaliland's total population at the time, of 640,000 (18.75%).[2]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]The Sultanate of Gerad Dhidhin was established in northern Somalia in the late 13th century by a group of Somalis from the Warsangali branch of the Darod tribe, and was controlled by the descendants of the Gerad Dhidhin. The Warsangali Sultanate included the Sanaag region and sections of the country's northeastern Bari region, which was traditionally known as Maakhir or the Maakhir Coast.[3]

The Sultanate is recognized for its remarkable longevity as a political entity and its tendency to prioritize trade over conquest or expansionism. The Sultanates major ports included Maydh, Bosaso and finally Laasqoray, its capital.[4] It was through these ports that they made the bulk of their trade revenue. I.M. Lewis, in his book A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa, mentions the sultanates reliance on their ports and writes:

Sultanates such as these, generally only arose on the coast or through commanding an important trade route, and were largely dependent on the possession and control of a port or other exploitable economic resources. They were in direct trade and diffuse political relations with Arabia, received occasional Arab immigrants, and were the centres from which Islam expanded with trade into the interior.

— I.M. Lewis, A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa, pg. 209

During the 19th century, Somali sultanates began to face pressure from European imperialism. I.M. Lewis points to the Sultanate's declining strength was due to the British Protectorate. Lewis writes:

Vestiges of a similar degree of centralized administration on the pattern of a Muslim Sultanate, survive today in the Protectorate among the Warsangali. Prior to 1920, the Garaad had at his command a small standing army with which, with British support, he fought Sayyid Mahamad Abdille Hassan's forces. But Garaad's powers' are dwindling under modern administration.

— I.M. Lewis, A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa, pg. 209

British-Warsangali Treaties

[edit]Under threat of violence from the British Empire, several northern Somali sultanates, including the Warsangali Sultanate, signed numerous treaties that led to the establishment of the British Somaliland protectorate in 1887.[3] I.M. Lewis mentions the Warsangali as being the most powerful of the sultanates within the British Protectorate.

Finally in the Protectorate, the Garaad of the Warsangeli, the most celebrated and strongest of northern Sultans, is recognized by the Administration and receives a salary.

— I.M. Lewis, A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa, pg. 205

Warsangali treaty with the British government[6][7]

The British Government and the Elders of the Warsangali tribe who have signed this Agreement being desirous of maintaining and strengthening the relations of peace and friendship existing between them;

The British Government have named and appointed Major Frederick Mercer Hunter, C.S.I., Political Agent and Consul for the Somali Coast, to conclude a Treaty for this purpose. The said Major F. M. Hunter, C.S.I., Political Agent and Consul for the Somali Coast, and the said Elders of the Warsangali, have agreed upon and concluded the following articles:-

ART.

I. The British government, in compliance with the wish of the undersigned Elders of the Warsangali, undertakes to extend to them and to the territories under their authorities and jurisdiction the gracious favour and protection of Her Majesty the Queen-Empress.

II. The said Elders of the Warsangali agree and promise to refrain from entering into any correspondence, Agreement, or Treaty with any foreign nation or Power, except with the knowledge and sanction of Her Majesty's Government.

III. The Warsnagali are bound to render assistance to any vessel, whether British or belonging to any other nation, that may be wrecked on the shores under their jurisdiction and control , and to protect the crew, passengers, and cargo of such vessels, giving speedy intimation to the Resident at Aden of the circumstances; for which act of friendship and good-will a suitable reward will be given by the British Government.

IV. The Traffic in slaves throughout the territories of the Warsangali shall cease for ever, and the Commander of any of Her Majesty's vessels, or any other British officer duly authorized, shall have the power of requiring the surrender of any slave, and of supporting the demand by force of arms by land and sea.

V. The British Government shall have the power to appoint an Agent or Agents to reside in the territories of the Warsangali, and every such Agent shall be treated with respect and consideration, and be entitled to have for this protection such guard as the British Government deem sufficient.

VI. The Warsangali hereby engage to assist all British officers in the execution of such duties as may be assigned to them, and further to act upon their advice in matters relating to the administration of justice, the development of the resources of the country, the interests of commerce, or in any other matter in relation to peace, order, and good government, and the general progress of civilization.

VII. This Treaty to come into operation from the 27th day of January, 1886, on which date it was signed at

Warsangali-Dervish collaboration

[edit]In his paper The 'Mad Mullah' and Northern Somalia, the historian Robert L. Hess touches upon this alliance, writing that "in attempt to break out of Obbian-Mijertein encirclement, the Mullah sought closer alliances with the Warsangali of British Somaliland and Bah Geri of Ethiopia".[8] In May 1916 the Dervish attacked Las Khorey but were repelled by a British Warship. In September of that year fearing a Dervish invasion, British troops occupied Las Khorey at the insistence of Sultan Mahamud Ali Shire.[9]

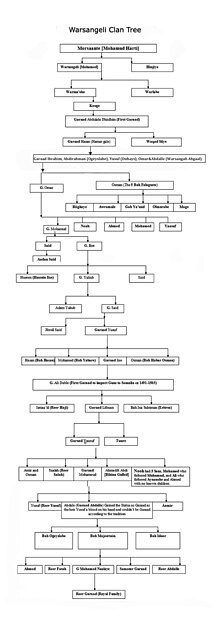

Sultans

[edit]

Rulers of the Warsangali Sultanate:[10][11]

| 1 | Garaad Dhidhin | 1298–1311 | Established the Warsangali Sultanate in the late 13th century. |

| 2 | Garaad Hamar Gale | 1311–1328 | |

| 3 | Garaad Ibrahim | 1328–1340 | |

| 4 | Garaad Omer | 1340–1355 | |

| 5 | Garaad Mohamud I | 1355–1375 | |

| 6 | Garaad Ciise I | 1375–1392 | |

| 7 | Garaad Siciid | 1392–1409 | |

| 8 | Garaad Ahmed | 1409–1430 | |

| 9 | Garaad Siciid II | 1430–1450 | |

| 10 | Garaad Mohamud II | 1450–1479 | |

| 11 | Garaad Ciise II | 1479–1487 | Father of Garaad Ali Dable. |

| 12 | Garaad Omar | 1487–1495 | Following Garaad Ciise II's death, various pretenders to the throne battled each other to succeed the ruler. Power was eventually transferred for a short period to Ciise II's brother, Garaad Omar. |

| 13 | Garaad Ali Dable | 1491–1503 | Exiled in Yemen after the death of his father, Garaad Ciise II. Returned with cannon fire and defeated the Garaad of Dhulbahante's troops in the Battle of Garadag. |

| 14 | Garaad Liban | 1503–1525 | Eldest son of Garaad Ali Dable. |

| 15 | Garaad Yuusuf | 1525–1555 | |

| 16 | Garaad Mohamud III | 1555–1585 | |

| 17 | Garaad Abdale | 1585–1612 | |

| 18 | Garaad Ali | 1612–1655 | |

| 19 | Garaad Mohamud IV | 1655–1675 | |

| 20 | Garaad Naleye | 1675–1705 | |

| 21 | Garaad Mohamed | 1705–1750 | |

| 22 | Garaad Ali | 1750–1789 | |

| 23 | Garaad Mohamud Ali | 1789–1830 | |

| 24 | Garaad Aul | 1830–1870 | |

| 25 | Garaad Ali Shire | 1870–1897 | Father of Sultan Mohamoud Ali Shire, with whom he briefly engaged in a power struggle. |

| 26 | Sultan Mohamoud Ali Shire | 1897–1960 | Led the Sultanate during some of its most turbulent years. Fought against and signed treaties with the British. Eventually exiled to the Seychelles for ignoring imperial entreaties. |

| 27 | Sultan Abdul Sallan | 1960–1997 | |

| 28 | Sultan Siciid Sultan Abdisalaan | 1997–present |

See also

[edit]- Adal Sultanate

- Ajuran Sultanate

- Mohamoud Ali Shire

- Mohammed Abdullah Hassan – religious and nationalist leader

- Yusuf Ali Kenadid – founder of the Sultanate of Hobyo

- Somali aristocratic and court titles

- List of Muslim empires and dynasties

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

- Sultanate of Hobyo

- Majeerteen Sultanate

Bibliography

[edit]- Lewis. I. M. A Modern History of Somalia: Nation and State in Horn of Africa. Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1960.

- Lewis I.M. A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa

- Speke. John Hanning. "Sultan/Garaad Mohamoud Ali—Hidden Treasure—Royal Reception—Sultan Tries my Abban". What Led to the Discovery of the Source of the Nile. Edinburgh: Edinburgh William Blackwood and Sons 1864.

- Alinur, Said. "Abyssinian Invasion: Reminder of a Seven Century old Animosity". 17 January 2007. Source

References

[edit]- ^ Abdullahi, Abdurahman (2017). Making Sense of Somali History: Volume 1. London, United Kingdom: Adonis & Abbey publishers ltd. p. 63. ISBN 978-1909112797.

- ^ Lewis, I. M. (1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. James Currey Publishers. ISBN 9780852552803.

- ^ a b Surhonee, L.M.; Timpledon, M.T.; Marseken, S.F. (2010-07-03). Warsangali Sultanate. VDM Publishing. ISBN 978-6130586324.

- ^ Briggs, Philip (2012). Somaliland : with Addis Ababa & Eastern Ethiopia. Internet Archive. Chalfont St. Peter, Bucks, England : Bradt Travel Guides ; Guilford, CT : Globe Pequot Press. pp. 10–12. ISBN 978-1-84162-371-9.

- ^ Lewis, Ioan M. (1999). A pastoral democracy: a study of pastoralism and politics among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. Classics in African anthropology (3. ed. - Repr. d. Ausg. von 1982 ed.). Hamburg: LIT. ISBN 978-3-8258-3084-7.

- ^ "Heshiiskii 27kii January, 1886". allsanaag. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ "Agreement between Great Britain and the Warsangali (Somali Coast), signed at Bunder Gori, 27 January 1886". Oxford Public International Law. Oxford Historical Treaties. 1886-01-27. Retrieved 2023-04-15.

- ^ Hess, Robert L. "The 'Mad Mullah' and Northern Somalia" (PDF). Journal of African History. 1964: 423. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ "King's College London, King's collection : Ismay's summary as Intelligence Officer (1916–1918) of Mohammed Abdullah Hassan".

- ^ "Sultan of Warsangali, Somalia". The African Royal Families. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ ""Rulers of the Warsangali Sultanate"" (PDF). Ferroon11. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ "Warsangeli Sultanate (Sultanate of Northern Somalia)".